One of her cadets, now an officer, wrote to his former professor about his experience in the active military preparing for his combat assignment and wondering if his lack of faith in the mission was a sign of disloyalty. “When I decided to teach English, I did not anticipate that I would be in the business of dispensing this sort of advice—on scanning Alexander Pope, perhaps, or unpacking a metaphor in an Elizabethan sonnet—but not this.” (page 163)

I found the book in the used book sales racks of the Brigadier General John C. L. Scribner Texas Military Forces Museum at Camp Mabry in Austin. After finishing it the first time, I read it again, making extensive notes, both on stickies and as marginalia. There’s a lot to think about. On almost every page, I found something to underline.

Dr. Elizabeth Samet (b. 1969) finished a BA in English at Harvard (1991) before earning her Ph.D. at Yale. She then joined the faculty of English and Philosophy at West Point (1996) and is now the chair of the English side of that department. The latest entry in her bibliography is an annotated edition of the The Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (Liveright Norton, 2019). She says in Soldier’s Heart that Grant’s Personal Memoirs was her gateway to the military. “I don’t remember who introduced us [in 1994 or 1995], but I can recall what an inspiring companion he proved to be after a few years on the obligatory graduate school diet.” (page 35)

At the end, she offers several pages of recommended reading. But recommended reading is actually the superstructure of the narrative, the framework of her coursework for West Point cadets. And she tells her story from several perspectives: Not Your Father’s Army; “Books are Weapons”; Becoming Penelope, the Only Woman in the Room; To Obey or Not to Obey; Bibles, Lots of Bibles; The Courage of Soldiers; The Anatomy of Sacrifice. Those spaces are arched by a Prologue (Year of the Plague) and an Epilogue (Ave Atque Vale). The stories stand alone, though some characters re-appear.

“This is a story about my intellectual and emotional connections to military culture and to certain people in it, but the real drama lies in the way the cadets I teach and the officers with whom I work negotiate multiple contradictions of their private and professional worlds. … Because they serve at the bottom of a hierarchy not especially interested in their opinions, cadets, especially plebes, at once crave and fear the freedom to wonder. … Few people know this part of their story: the courage with which they challenge accepted truths; the nuanced way they read literature and culture; and the ingenious methods they have for resisting conformity in lives largely given over to rules and regulations. Our national fondness for celebrating the physical heroism of soldiers—the apparent readiness with which they sacrifice their lives to larger causes—eclipses the far less romantic displays of moral and intellectual fortitude that also distinguishes so many of them. In turning them all into heroes, we have lost the sense of the individuality they also fight to preserve.” (page 13)

The title comes from one of the earliest descriptions of what we now call PTSD. It has been termed shell shock and battle fatigue. The diagnosis “soldier’s heart” followed the American Civil War. It mimicked cardio-vascular disease but insightful practitioners recognized that the problem was psychological, not organic. Samet extends that meaning by recording, reflecting on, and honoring the emotional hearts of soldiers. Though she does invest much in our unresolved relationships with and distinctions between the wounded and the dead (Chapter 7), this book is really a celebration to the living. It honors the young officers who choose the difficult and sometimes impassable roads to the moral high ground in a morally ambiguous world.

“I often get the feeling that these officers have something they want to say but can’t. Perhaps they simply want to acknowledge the change, to resume a normal acquaintance, or to tell me about something that happened in the desert. Whatever they know cannot be pried loose by a lot of questions. It has to come voluntarily and perhaps only much later, when distance permits reflection. More often than not we end up talking about where they read a particular book and what they found in it that helped them better understand what they have been asked to do. Thus when people ask me about my ‘function’ I can’t answer so glibly because when I look out at those newly shorn plebes who appear so eager to please on the first day of the semester, full of good faith and idealism, I see not simply students of literature or numbed soldiers but citizens who are willing to make a very real sacrifice.” (page 15)

Writing in 2007, she called it the Long War (page 11). Soldiers now call it The Forever War after Haldeman’s book. In 2016-2017, the Texas State Guard assigned me a fulltime opportunity to work in the Domestic Operations Task Force of the Texas Military Department. My commanders included young lieutenants who never knew a time of peace and now are not likely to as they mature up the ranks. Consequently, this is a book for everyone who wants to understand their responsibilities as citizens in a republic that chooses to go to war.

Author:

Willing Obedience: Citizens, Soldiers, and the Progress of Consent in America : 1776-1898, Stanford Univ. Press, 2004. (This grew out of her doctoral dissertation.)

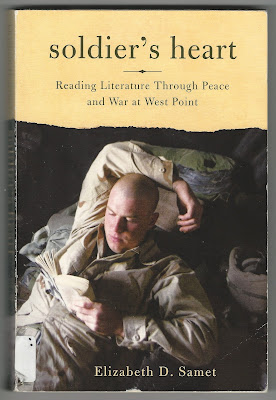

Soldier's Heart: Reading Literature Through Peace and War at West Point, Picador, 2008.

Leadership: Essential Writings by Our Greatest Thinkers: A Norton Anthology, 2015.

No Man's Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America, Picador USA, 2015.

The Annotated Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Liveright W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Contributor:

Thomas Jefferson's Military Academy: Founding West Point by Robert M. S. McDonald, University of Virginia Press, 2004.

Tolstoy on War: Narrative Art and Historical Truth in "War and Peace" by Rickie Allen McPeak, Cornell University Press, 2012.

PREVIOUSLY ON NECESSARY FACTS

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.