Commandos,

Green Berets, Rangers, SEALs,… military special forces are legendary. We look

to them for lessons, as examples to follow, as paradigms for living. Businesses

want their managers to be leaders worthy of the most dangerous and demanding

work we can imagine in service to our highest values of nation and family,

liberty and democracy. We would find it unusual, even unsettling, if military

commanders exhorted their field officers to be profitable, productive, and

thrifty. (See “Choose Your Virtues” and

“Shifting the Paradigm of Private Security” here.) The

military is a model for business. The merchant ethos does not inform the

military.

|

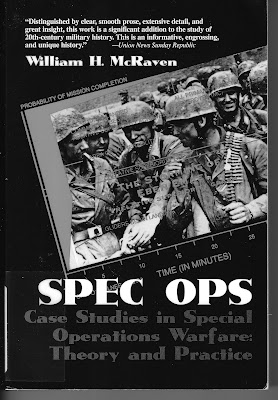

| Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Warfare Theory and Practice by William H. McRaven (Random House 1995; Ballantine Books 1996). |

These

narratives are interesting on their own merits.

The German assault on the Belgian fort Eben Emael in WWII was pure blitzkrieg. Italian frogmen attacking

the battleship Queen Elizabeth in

Alexandria, and British midget submarines hitting the Tirpitz at Kaafjord, Norway, are almost science fiction. The

American liberation of POWs in the Cabantuan camp in the Philippines and the

failed mission at Son Tay, Vietnam, could have come from Hollywood. The Israeli

raid to free hostages held by the PFLP at Entebbe in Uganda was retold in two

movies and a TV series. Action and adventure aside, McRaven chose them and

others to demonstrate his theory of special operations.

Not

all of the missions exemplified the fullest use of all factors. The British

raid on the Saint-Nazaire dry docks called for over 600 men, 18

attack boats, and a destroyer. McRaven labeled it a success because the primary target was

achieved: the dry dock mechanical works were wrecked. However, the

over-ambitious inclusion of many subsidiary goals only left a lot of men dead

and a few men captured.

It

is clearly a challenge, perhaps impossible, to bring a large force to the expert

effectiveness of commandos. But there are lessons here for the individual.

You are a small unit. You have good internal communication. You can identify your own mission, create a plan, and exercise it. You know your mission, and you are dedicated to it. And you are authorized to improvise as needed in the face of contingencies. You can plan and train in secret. You can do this every day.

Your skills may be common, but the full set of them is unique to you. How you put them to work is also special. Rather than blowing things up – though Austrian economists speak of “creative destruction” – most of us build, create, deliver, and maintain. It can still be special operations if you bring that intention to your work.

You are a small unit. You have good internal communication. You can identify your own mission, create a plan, and exercise it. You know your mission, and you are dedicated to it. And you are authorized to improvise as needed in the face of contingencies. You can plan and train in secret. You can do this every day.

Your skills may be common, but the full set of them is unique to you. How you put them to work is also special. Rather than blowing things up – though Austrian economists speak of “creative destruction” – most of us build, create, deliver, and maintain. It can still be special operations if you bring that intention to your work.

PREVIOUSLY ON NECESSARY FACTS

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.